Old sketches, maps and gothic effigies unlock secrets of John Keats’s famous poem ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’

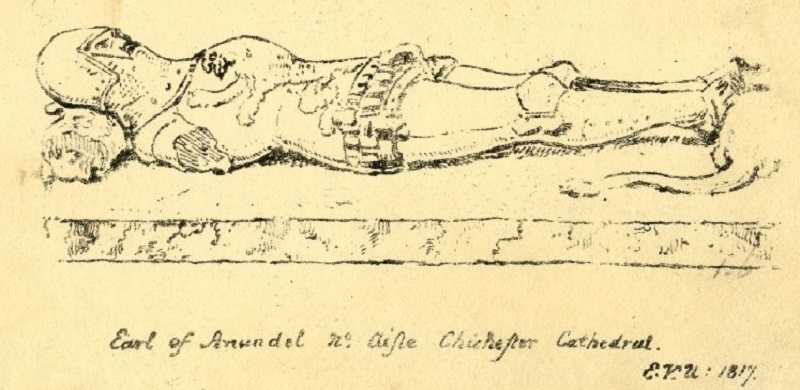

Edward Vernon Utterson: sketch of the Tomb of the Earl of Arundel in Chichester Cathedral, with effigy as a knight, head to left, his right arm missing. Made in 1817 (two years before Keats visited) © Trustees of the British Museum

16 May 2019

New work by Aberystwyth University researchers suggests that two hand-holding gothic effigies in Chichester Cathedral made famous by Philip Larkin’s poem ‘An Arundel Tomb’ also inspired John Keats’s 200-year-old meditation on doomed love, ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’.

Scholars have long assumed that the poem’s haunted Knight-at-arms and enchanting Belle Dame were faux-medieval literary confections.

New research by Professor Richard Marggraf Turley and MA student Jennifer Squire from the Department of English and Creative Writing at Aberystwyth suggests both figures were inspired by the alabaster effigies of Richard FitzAlan and Eleanor of Lancaster in Chichester Cathedral.

Professor Marggraf Turley and Jennifer Squire will present their findings at the Keats Foundation’s 6th Bicentennial International John Keats Conference at Keats House, Hampstead, in London, on Sunday 19 May.

When Larkin visited Chichester Cathedral in 1956, the medieval effigies of Richard FitzAlan in full knight’s armour and his wife Eleanor of Lancaster had been restored by the Victorians.

Lying ‘side by side’ and hand-in-hand, the pair presented Larkin with an image of enduring devotion (‘What will survive of us is love’).

As forgotten amateur sketches from Keats’s day show, when Keats visited in 1819, the statues were not arranged side by side, but had been torn apart and lay head-to-toe, pushed up against a wall.

The love-struck knight-at-arms was in fact a ‘knight-without-arms’, missing the limb that joined him to his wife – adding a layer of irony to Keats’s description of the knight.

The not yet restored effigies – haggard from lying outside in the elements for a century, and separated by a pillar – resonated with Keats’s personal situation.

Professor Marggraf Turley said: “Illness and financial difficulties prevented Keats from marrying his next-door neighbour and great love, Fanny Brawne. The medieval statues became sepulchral avatars for Keats and Fanny.

“Generations of Keats fans have associated ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’ with Hampstead Heath, round the corner from Keats’s and Fanny’s Hampstead house. Our research suggests that the desolate landscapes of Keats’s ballad were actually drawn from Bedhampton, a village thirteen miles from Chichester.

“Key elements of the ballad – meads, a granary, sedgy lakes and a hill side – are all to be found near to Keats’s lodgings in Bedhampton, and explain another layer of symbolism in Keats’s anquished lament for doomed lovers.”

Professor Richard Marggraf Turley is Professor of English Literature at Aberystwyth University. He is author of several books on the Romantic poets, including Keats’s Boyish Imagination (2004), Bright Stars: John Keats, Barry Cornwall and Romantic Literary Culture (2009), and Keats’s Places (2018). He is also author of a historical crime novel set in London in 1810, The Cunning House (2015). In 2007, he won the Keats-Shelley Prize for Poetry.

Jennifer Squire is a Masters student in the Department of English and Creative Writing at Aberystwyth University. She is working on depictions of nervous disorders in the Romantic era and the novels of Jane Austen.