Biological clocks keep ticking in the high Arctic summer

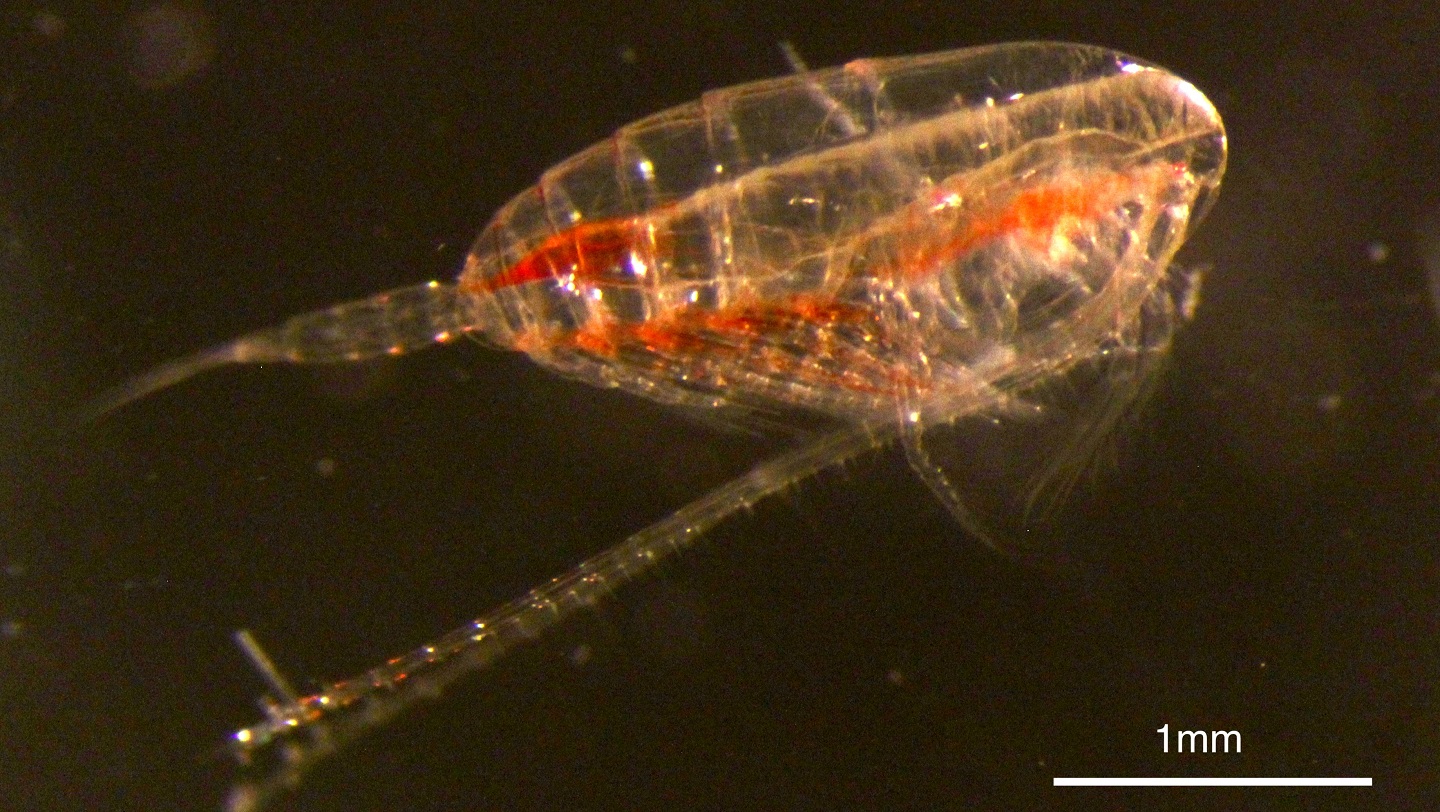

Image of Calanus finmarchicus (copepod), the study organism. (Photo- Lukas Hüppe)

15 July 2020

Researchers have found that the natural biological clocks of tiny marine organisms continue to function even in the Arctic summer when the sun doesn’t set.

Their findings are part of a wider study looking at the impact of climate change on the Arctic Ocean’s ecosystem.

By understanding more about the circadian rhythms of Arctic marine life, the scientists hope to more accurately predict how its ecosystem will respond to the challenges of warming waters and reducing sea ice.

In a paper published today (Wednesday 15 July 2020) in The Royal Society Biology Letters, they outline how the biological clocks of tiny planktonic crustaceans known as copepods keep ticking even when day and night are indistinguishable.

The paper is the first in a series of studies carried out during a UK research cruise into the high Arctic Ocean in summer 2018 by an international team from Aberystwyth University, the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) and the Helmholtz and Alfred Wegener Institutes, Germany.

Dr Kim Last from the Scottish Association for Marine Science and lead co-investigator on the project said: “It’s simply astonishing to know that these tiny copepods, have a functioning clock when they can be tens to hundreds of meters underwater and sea-ice at a time when there is virtually no difference between day and night.

“Climate change is allowing these copepods to migrate northwards into habitats with extreme annual day/night cycles. Their ability to adapt (their clock) may give them an edge over resident copepods ultimately influencing the structure of the Arctic food web.”

Dr David Wilcockson, a marine biologist based at Aberystwyth University’s Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS), is a co-author of the paper.

“We know that many coastal marine organisms have tidal as well as circadian clocks. These oceanic, Arctic copepods may have the ability to modify or switch between clocks depending on where they end up and the conditions they are challenged by,” said Dr Wilcockson.

Intriguingly, the researchers found that whilst in the southern Arctic, circadian clock genes generally cycled over a daily period. However,in the northern Arctic and only a few hundred miles from the North Pole, this pattern changed.

Lukas Hüppe, lead author of the study and Research Associate at the Helmholtz Institute for Functional Marine Biodiversity and the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, said: “We noticed that the circadian clock had changed from mostly 24 hours to 12 hours. We assume this means that the animals are using other signals to set their clock which can potentially include the tides.”

Copepods are essential to the Atlantic and Arctic food webs because of their large lipid reserves and as the main food source for fish and many sea birds and whales. The team’s findings will provide clues on their survival at very high latitudes.

The research is supported by the CHASE project, part of the Changing Arctic Ocean programme, and jointly funded by the UKRI Natural Environment Research Council (NERC, project number: NE/R012733/1) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, project number: 03F0803A). Cruise time on the British Antarctic Survey Research Vessel James Clark Ross was supported by the CAO Arctic PRIZE project (NERC: NE/P006302/1).