Understanding Earth's fiery cousin

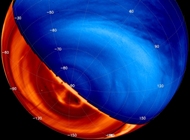

Venus. Credit: ESA/VIRTIS and VMC teams

29 November 2007

Thursday 29 November 2007

Understanding Earth's fiery cousin

Latest results from Venus Express

It has long been thought that Earth and Venus should be similar, but results from the European Space Agency's (ESA) Venus Express spacecraft, published in Nature (29th November 2007), show how different they really are.

Venus Express, which was launched in November 2005, has been providing data on Earth's fiery cousin since arriving in Venus's orbit in April 2006. The latest findings appear in a special section of the 29th November issue of Nature containing nine individual papers devoted to Venus Express science activities - providing the most detailed picture of the planet to date.

One of the authors is Professor Manuel Grande, Head of Solar System Physics research group at the Institute of Mathematical and Physical Sciences at Aberystwyth University.

Professor Grande is a co-investigator on the ASPERA-4 instrument, which is mounted on Venus Express and designed to look at the make-up of space just above the Venusian atmosphere.

“This is a dynamic region where the ‘solar wind' of charged particles from the Sun interacts with top of the atmosphere. This doesn't happen at Earth because we are protected by the Earth’s magnetic field. However, on Venus the action of the Solar Wind is to remove material from the top of the Atmosphere,” he said.

“What’s important about the new results is that they show that the material is removed in the ratio H2O. In other words it is losing water. Actually Venus has very little water left. It is an extremely hot unpleasant place, with a runaway ‘greenhouse effect’. This suggests that the water has been lost to space, rather than for example incorporated into minerals on the planet’s surface. It escapes as ions, two hydrogen ions for every one oxygen ion.

“ASPERA-4 consists of a suite of instruments which look at atoms, electrons and ions in the bit of space near to Venus. In many ways it turns out to be quite different to the space near Earth, much more like that close to Mars or a comet. Here at Aberystwyth we are responsible for looking after the detectors in the part of the instrument which looks at atoms,” he added.

Studying the ionosphere (the ionized upper atmosphere) of Venus builds on the great tradition of Aberystwyth in studying the Earth’s ionosphere, and of course, looking at a different system also helps us to understand our own system better. Studying Venus forms an important strand in the successful proposal which brought £2.25 million to the Institute of Mathematical and Physical Sciences in 2006 for a coordinated programme of Solar system research.

Venus is often referred to as the Earth’s sister planet because of its similarities in size, mass, density and volume. At an average distance of 108 million km from the Sun, it is about 30% closer than the Earth. However, Venus has no surface water, and has a toxic, heavy atmosphere made up almost entirely of carbon dioxide and it rains sulphuric acid. The surface of the planet is the hottest in the solar system at a searing 750 K (477 °C) which has been caused by a catastrophic greenhouse effect due to the carbon dioxide rich atmosphere.